The essence of taste is discrimination

not liking good art

Naomi Kanakia articulates a view of taste that I think is quite common among creatives:

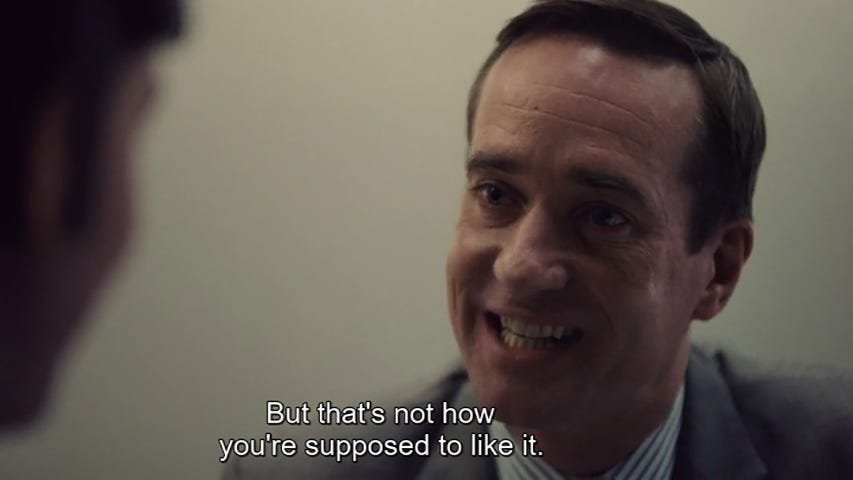

The idea that good taste is about finding things that are objectively good has many defenders. This makes sense. If you admit that you can’t sustain total aesthetic relativism – that in some true sense, Shakespeare is better than the trashy romantasy you love to hate – then you quickly arrive at a view in which some art is better than others. From there, it’s only natural to try and seek out good art, and attempt to enjoy it even if that enjoyment doesn’t strike you naturally. In this model, good taste (yours or others) is the compass that leads you towards what is better, and away from what is worse.

But I disagree with this view. Instead, I propose a different criterion: good taste is about being able to discriminate between two subtly different experiences.

In the cookbook Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, Samin Nosrat relates an anecdote about the legendary chef Alice Waters. While judging tomato sauce recipes to be used at her restaurant, Waters rejects an otherwise-excellent submission because she can taste that the chef used old olive oil to make the sauce. Even through the intense flavors of tomato and garlic and onion, Waters could identify the qualities of the olive oil. That discernment is the sign of good taste.

Some discrimination is easy and requires no taste (separating a Monet from a child’s doodle). Other discrimination is hard and requires taste (separating a tomato sauce with old oil from a tomato sauce with fresh oil). The closer two experiences are, the harder it is to discriminate between them, and the better a sign of taste it is if someone can discriminate between them. At the highest level, a sommelier has passed an exam that requires them to blindly identify which grape is in a wine that they taste, which year it was from, and even where it was grown. In a model of taste that centers discrimination, that skill is the purest demonstration of taste.

Of course, when it comes to literature, I use “discrimination” more broadly than just the narrow concept of distinguishing between two different experiences (which is more appropriate for the culinary examples above). In general, discrimination is about having a deep mechanistic understanding of that experience – understanding how different choices would have led to a different experience. We rarely ask critics to read a story blind and tell which author wrote it (though I think that would be an interesting test of taste!), but we do ask that critics can explain why an author chose to have some action happen in the story, or why the relationship between two characters mattered.

II

A notable absence from this model of taste is opinion. Having a deep mechanistic understanding of a work of art does not imply that you like it. Can you identify what the author is trying to do with this paragraph or this flashback? Then you have demonstrated taste, whether you actually like the story or not.

This runs the risk of claiming that there is no such thing as good art. I do not believe that. I agree with Kanakia that people with good taste usually arrive at roughly similar rankings of writers, and those rankings are accurate in marking writers as better or worse. My claim is just that liking good art is not the same as having good taste. It is entirely possible for someone without taste to enjoy good art; their lack of taste would reveal itself only if they were asked to explain what they enjoyed about it. When I was 15, I “read” Crime and Punishment, in the sense that I read one page and then another and then another until I reached the final page. I even enjoyed reading it. But I couldn’t tell you why, because I didn’t really understand the story at all. Dostoyevsky may be a genius, but enjoying Dostoyevsky did not imply that I had good taste.

“Good taste is not about liking good art, it’s about [process that usually leads to liking good art]” may strike you as pedantry. But the process is what matters. That is why I react strongly to a statement like “you should like [author], because many people with good taste have said they are good.” I don’t doubt that most subjects of a statement like that are great authors, and that I might even love them. But we come to art to explore our souls. As Ava says, “interiority is not formulaic. You can look to other people for inspiration, but they can’t tell you what is true for you.”

The ability to discriminate frees you from the gaze of other people as your only window into art. It allows you to connect with art without needing an authority to validate that connection. Without the ability to discriminate, you depend on other people to show you what is good; you depend on them to understand your own soul.